In April 2025, the RCP hosted a workshop that explored how the NHS can respond to the government’s promised ‘hospital to community’ shift in care – the so-called ‘left shift’. With over 40 participants, including clinicians, patient representatives, national charities, royal colleges and policymakers, the event has resulted in a new toolkit – Time to focus on the blue dots – which calls for a fundamental shift in how the NHS delivers care.

Opening the workshop, Dr John Dean, RCP clinical vice president, introduced Prescription for outpatients, the RCP’s vision for the future of planned specialist care. Describing collaboration between the medical specialties, primary care and patient organisations as ‘crucial’, Dr Dean talked about the UK government’s 10 Year Health Plan as an opportunity to drive reform.

Samantha Mauger, chair of the RCP’s Patient and Carer Network (PCN) emphasised the importance of delivering care closer to home. ‘Patients want a personalised joined-up approach that enables them to feel comfortable in their surroundings,’ she explained. ‘Whether it’s receiving hospital-level treatment at home or having honest conversations in the last year of life, people want to be cared for in familiar environments, supported by trusted professionals.’

The right care, from the right person, in the right setting

Dermatologist Dr Tanya Bleiker explained that to enable early diagnosis, timely treatment, and the best possible outcomes, patients need to see the right person, at the right time. Every patient encounter must add clinical value; we must eliminate those consultations that offer little benefit and instead design care around what patients actually need at each point in their journey. The ‘right person’ might be a GP, specialist, nurse, or allied health professional, and care should be delivered as close to the patient as possible. Flexibility is essential, both in terms of who delivers care and where it's delivered, recognising that needs will change over time. We must also respect patients’ time, ensuring appointments are purposeful and appropriate. Achieving this will require reform of commissioning and funding models to better support value-based, flexible care. It also means ensuring every professional works to the top of their licence and that administrative burdens are minimised, so we optimise the time of the most appropriately trained clinicians towards delivering care

Sarah Tilsed, head of patient partnership at The Patients Association suggested that outpatient care should be flexible and fit around people’s daily lives, including work or caring responsibilities, rather than relying solely on traditional face-to-face appointments. Clinicians must be supported with training in areas such as cultural competency, co-production, the use of artificial intelligence (AI), and shared decision-making to help tackle health inequalities. Patients need access to clear information and to knowledgeable, well-trained staff, including administrative roles like patient navigators. Empowering patients to take an active role in their health can improve outcomes and reduce pressure on overstretched services. This is particularly important for people living with long-term conditions, where continuity, confidence and proactive care can make a lasting difference.

Neurologist Dr Fiona McKevitt told attendees that we need to improve communication. Patients consistently report feeling poorly informed. They are often unsure why they had been referred to outpatients, unaware of when their appointment would be, or left in the dark about what to expect in terms of investigations or treatment. Digital tools such as patient portals or the NHS app could play a valuable role in improving access to information. We also need to ensure smooth, accurate, and timely communication between healthcare professionals, which is essential to providing continuity of care, reducing errors, avoiding unnecessary delays, and ultimately improving patient outcomes and experience.

RCP clinical lead for outpatient care Dr Theresa Barnes asked the room to move beyond thinking of outpatient care solely in terms of appointments. The focus should be on defining the purpose of each interaction and then determining the most appropriate method and team member to deliver it. Remote consultations, when clinically appropriate, can save patients time and stress, but care can also be progressed through other means such as virtual MDT clinics, asynchronous communication via patient portals, and remote sharing of data or images. These activities must be recognised in clinician job plans and supported by commissioning models that focus on outcomes. Integrated pathways – across primary and secondary care, and within specialties – can reduce duplication and clarify roles. Finally, care coordination and patient navigation are essential, particularly for the small proportion of patients who generate the majority of activity due to complex clinical and social needs.

‘Digital systems must be designed to actively enable better, more personalised and efficient care, not just digitise existing processes,’ explained Dr Anne Kinderlerer, RCP digital health lead. Clinicians need access to longitudinal patient data across GP and hospital settings to understand what treatments have worked and identify gaps in care. Systems must also support population-level analysis to identify patients most in need of specialist intervention. Current outpatient data are limited, but integrating referral reasons, diagnoses, and outcomes could transform clinical insight. Interoperable records are essential, allowing clinicians to see a complete picture of patient care regardless of setting. With these provisions in place, AI could support earlier risk detection, streamline decision making, and reduce clinician workload, for example, by generating structured notes, patient letters, and follow-up actions using voice recognition. Digital tools have the potential to significantly improve patient care and clinician experience if they are co-designed with staff and clinicians and integrated iteratively into clinical workflows.

What does this mean for patient care?

The audience discussion highlighted the need to strike a careful balance between efficiency and safety. Working at the top of one’s licence is important for making best use of professional skills, but we must remain alert to the risks – particularly the potential for fragmentation and delays caused by a lack of continuity, especially in complex community-based care for older people. Flexibility must be underpinned by clear governance, shared understanding of roles, and a strong foundation in personalised care skills.

Clinicians need support and training to develop these skills. We must redesign digital tools, job plans and governance structures to support safe, team-based care that prioritises continuity and relationships. Asynchronous communication – via texts or messaging apps – can keep patients with unstable conditions out of hospital but must be supported by systems that make it easy to document, log, and safely respond to such interactions. Ensuring everyone can harness population-level data is essential to reducing unwarranted variation.

Making neighbourhood health the norm

Sir John Oldham, strategic adviser to the secretary of state for health and social care, challenged the room to rethink how we deliver care for people with complex needs.

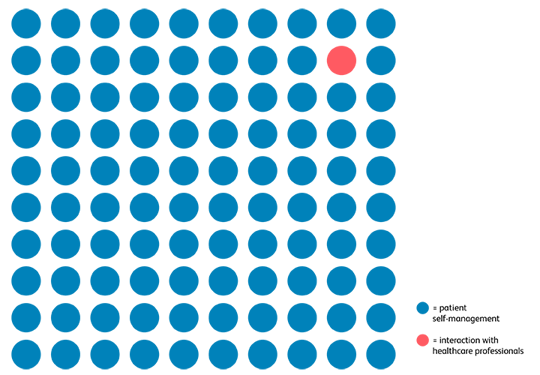

‘If you bring into your mind’s eye a sheet of paper full of blue dots with one solitary red dot,’ he explained, ‘the blue dots represent the hours in the year a patient has to manage their condition themselves. The red dot represents the time they interface with health professionals. Yet 99.99% of our time, effort, resource and management is on the red dot. Perhaps it’s time we focused on the blue dots.’ This requires coordinated action across statutory and voluntary sectors.

‘Relationships, not structures, are the key,’ he added. ‘The NHS must now scale what already works through a large-scale neighbourhood health programme that enables integrated, person-centred care to become the norm.’

From vision to reality

Across Kingston and Richmond, anticipatory care MDTs are helping patients with frailty stay well in the community. Similar models – such as Connecting Care for Children – bring secondary care expertise into primary settings. In the St George’s headache hub, collaborative triage and group clinics provide timely, expert-led support while maximising clinical capacity.

Dr Shelagh O’Riordan suggested that we must do less in hospital – not simply add more in the community on top of business as usual. ‘Hospital at Home’ services deliver hospital-level care directly in patients’ homes, either as an alternative to admission or to enable earlier discharge. This model enables faster recovery, greater independence, and far fewer complaints or clinical incidents than traditional inpatient care. It is well-liked by patients, supported by growing international evidence, and significantly more cost-effective.

‘We can no longer sustain the current model of end-of-life care, which over-relies on acute hospitals and underinvests in community services,’ explained Professor Fliss Murtagh. ‘One in three hospital inpatients are in their last year of life, with over 70% of those who die having spent time in hospital in their final 6 months. This represents not only a major use of NHS resources – 30 million hospital bed days annually – but a profound mismatch with what people actually want,’ she added.

‘To meaningfully shift care from hospital to community, we must radically improve early identification of deteriorating health, invest in truly integrated and relational community care, ensure 24/7 crisis support, and improve communication so that people can plan and make informed choices about their care.’ – Professor Fliss Murtagh, professor of palliative care.

Evidence shows that terminally ill patients prioritise quality of life, yet they often receive fragmented, overly medicalised care, with little communication about deterioration or dying. Community services – GPs, district nurses, and specialist palliative care – are under-resourced and overstretched, offering only minimal support in the final months of life. Families are too often left to fill the gaps, often at great emotional and financial cost.

An NHS built on compassion, communication and collaboration

It’s time to move beyond the limiting language of ‘hospital’ and ‘community’, ‘specialist’ and ‘generalist’. The current constructs no longer serve us well.

We need to work together to describe and deliver a different NHS – that means honest conversations about funding and workforce, and a focus on what connects the system: relationships, communication, and shared purpose.

‘We must invest in people, relationships, and communication, supported by data, digital tools, and a shared commitment to care that truly revolves around patients and their lives.’ – Dr John Dean, RCP clinical vice president.

From the patient perspective, clear, compassionate communication and genuine shared decision-making are essential. Leadership, workforce training, and investment in community services must be prioritised. The message is clear: we cannot wait any longer.

With thanks to our speakers and panel members: Dr Theresa Barnes, Dr Tanya Bleiker, Dr John Dean, Dr Anne Kinderlerer, Samantha Mauger, Dr Fiona McKevitt, Sir John Oldham and Sarah Tilsed.

The RCP will use the findings from this workshop to influence change and improve care: the RCP Time to focus on the blue dots toolkit on designing care around people, not buildings is based on the input of more than 40 workshop participants, including patients, clinicians and representatives from specialist societies, royal colleges, national charities and the Department of Health and Social Care.

The RCP next generation oversight group (which includes medical students, doctors in training, locally employed doctors, specialist, associate specialist and specialty (SAS) doctors and consultant physicians) held a session beforehand to discuss the future of medical training in the context of the hospital to community shift. The insights from this session were shared with the workshop.

Case studies will be published on our quality improvement hub, Medical Care – driving change.