I grew up hearing my father’s stories – his dramatic escape from communal violence that erupted around the 1947 partition of India, his struggles and losses. Stories of his arrival in Britain with just £3.50 in his pocket and his time on the hospital wards in north Wales, where he quietly built a life of NHS service. His journey wasn’t unique. It’s one of thousands like it that have helped shape the NHS today, writes Dr Binita Kane, one of the co-founders of South Asian Heritage Month.

That’s why South Asian Heritage Month (SAHM) (18 July–17 August 2025) matters. It offers an opportunity for NHS organisations not only to celebrate and educate, but to reflect – on the histories, cultures and contributions of people from South Asia’s eight countries: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, the Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka.

The 2025 theme of SAHM, ‘Roots to Routes,’ is especially resonant in healthcare. It invites us to consider how the deep historical roots between Britain and South Asia have shaped the many routes taken by South Asians to help create, sustain and transform the modern-day NHS. It also compels us to reflect on how these histories – rooted in Empire, trauma and resilience – continue to shape health outcomes and workforce experiences today. With one in every 14 people in the UK being from South Asian heritage, this history is relevant to everyone working in healthcare.

Partition of India and the migration that followed

The roots begin in 1947, with the end of the British Empire in India. After 200 years of British rule, the British divided India on religious grounds, creating the new nations of India and Pakistan – a process that took just 10 weeks. The plan was announced on 3 June by Lord Mountbatten, the last viceroy of India. It received royal assent from King George VI on 18 July. The boundary demarcations drawn by Sir Cyril Radcliffe – who had never previously set foot in the subcontinent – came into effect on 17 August.

The consequences were seismic. 15 million were people displaced overnight, the largest forced migration in modern history. More than a million lost their lives. As borders were hastily drawn and communities uprooted, deep-seated religious tensions erupted into widespread communal violence. The trauma endured by those who lived through it shaped family narratives for generations, including my own story, and many others now working in UK health services.

In the wake of the World War II and the founding of the NHS in 1948, Britain looked to its former colonies for help. Recruitment campaigns encouraged Commonwealth citizens – doctors, nurses, midwives and porters – to come to the UK to fill urgent workforce shortages, and granted them citizenship through the British Nationality Act 1948. For many, this was an opportunity and a necessity; driven by political upheaval, economic instability and the need for security after the chaos of partition.

The routes that built the NHS

From the 1950s onwards, South Asian healthcare workers arrived in large numbers, often taking posts that were underserved, underpaid or unpopular among UK-trained peers. Many worked in areas of high deprivation or in roles deemed less prestigious, so-called ‘Cinderella specialties’ such as psychiatry or geriatric medicine. South Asian nurses and midwives also became integral to the day-to-day functioning of hospitals and community health services.

The contribution of overseas doctors was recognised early on; in a 1961 House of Lords debate, Lord Cohen of Birkenhead remarked that the NHS would have ‘collapsed without the influx of junior doctors from countries such as India and Pakistan’. By the 1970s, a third of NHS doctors had been recruited from abroad.

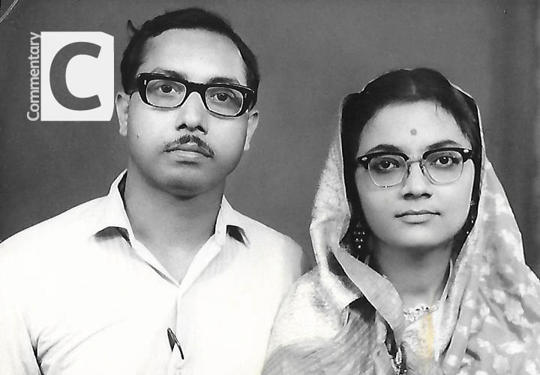

My own father, Professor Bim Bhowmick, a partition refugee, somehow survived starvation and abject poverty to qualify as a doctor in Kolkata. In 1969, he and my mother, also a doctor, migrated to the UK, each with £3.50 in their pockets.

Kolkata, India in 2013

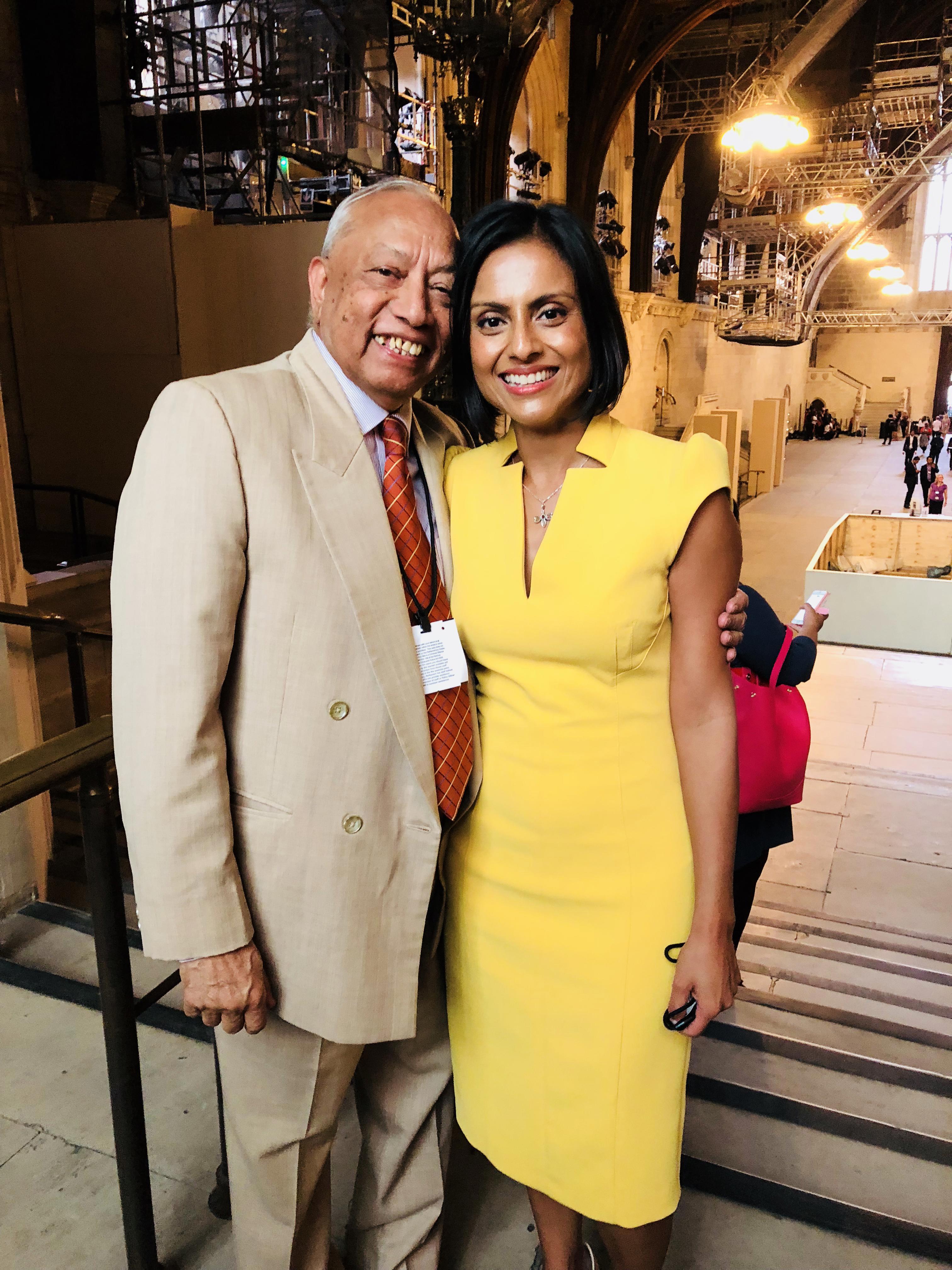

Despite being steered away from more prestigious roles, my father forged a pioneering career in geriatric medicine in north Wales. He went on to become the first minority-ethnic MRCP(UK) examiner and elected RCP councillor – and was a founding advocate for the RCP’s equity, diversity and inclusion work. He served the NHS for nearly 50 years and was awarded an OBE for his services – Empire, in a sense, coming full circle.

His story is not unique. Thousands of South Asian healthcare workers have similar stories of hard work, resilience and dedication in the face of adversity and racism, pioneering services for the NHS. Yet for too long, their contributions have gone unrecognised or been reduced to footnotes. SAHM challenges us to change that – to tell the full story and to ensure that these contributions are remembered with dignity and respect.

Dr Binita Kane and her father.

A legacy of inequality

But the legacy is not only one of service. It is also one of systemic inequality, both as patients and as healthcare staff. The disproportionately poor health outcomes among South Asians are well-documented, yet inequities also persist within the South Asian community itself. Much of this is rooted in the differing migration journeys, and the conditions and opportunities that migrants encountered upon arrival in the UK.

In the 1950s, many Pakistani migrants arrived from rural regions and entered industrial employment in the north of England, typically following a working-class trajectory. In contrast, Indian and urban Pakistani migrants – often from upper-caste or professional backgrounds – came during the 1950s and 60s as skilled workers; including doctors, engineers and academics. These groups were more likely to enter professional sectors and attain economic stability. Bangladeshi migration, largely originating from Sylhet, peaked in the 1970s – and was frequently driven by extreme poverty and political unrest. Many Bangladeshi migrants found work in low-paid sectors such as catering or textiles, and often settled in deprived urban areas, particularly in east London. These early occupational divides continue to shape access to housing, education and employment today – key social determinants of health.

These distinct migration experiences have contributed to persistent and deeply rooted health inequalities. Bangladeshi communities, in particular, remain among the most socioeconomically disadvantaged groups in the UK – facing elevated levels of unemployment, overcrowded housing and chronic health conditions. While all minoritised communities experience systemic disparities in health outcomes, the burden is especially acute among Bangladeshis. These differences underscore the urgent need to move beyond broad, reductive classifications such as ‘BAME’ and to acknowledge the intraethnic diversity within South Asian, Black and other racialised populations when addressing health inequalities.

These inequities extend into the NHS workforce itself. South Asian staff, despite their pivotal role in the health service’s development, continue to be underrepresented in leadership and disproportionately subject to disciplinary action. These disparities are not relics of the past but are reflected in current measurable outcomes, from NHS Workforce Race Equality Standards (WRES) data to the ethnicity pay gap. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on South Asian healthcare workers – with higher rates of mortality and occupational exposure – further highlights the structural inequalities that remain embedded in the system. These are not incidental. They are the cumulative results of longstanding structural inequalities that remain unresolved.

As a South Asian woman, witnessing the election of another South Asian woman as president of the RCP was both powerful and profoundly moving – a moment that, not long ago, would have felt unimaginable. This milestone stands on the shoulders of those who came before us; it is the result of the resilience, perseverance and quiet sacrifices of earlier generations. The hardships endured by my father’s generation helped to open doors, allowing mine to enter the profession with greater acceptance and opportunity. Representation matters not only because it inspires and empowers those who come after, but because it brings diverse perspectives that strengthen our profession to ensure it better reflects the society we serve. But representation alone is not enough, it must be accompanied by leadership committed to addressing the systemic biases that create unequal outcomes for both staff and patients. Crucially, those who rise must also create space for others.

Why this matters to everyone

This is not just a South Asian story. It is a British story. It is an NHS story. And it should matter to everyone who cares about fairness, inclusion and the delivery of high-quality care.

Understanding the ‘roots’ of South Asian presence in the NHS helps illuminate the ‘routes’ by which people came to serve and the systems that have sometimes failed them. It allows us to see health inequalities not as isolated statistics, but as the outcome of policy, history and social context. This is not at the exclusion of other minority ethnic groups; it is about all of our stories, which are deeply intertwined.

SAHM is not merely symbolic. It is a chance to foster cultural competence, acknowledge shared histories, promote integration and cohesion, and challenge the structures that reproduce inequity. When we take time to understand the stories of our colleagues and patients of all backgrounds more fully, we become better clinicians, better leaders and, ultimately, better advocates for change.

Many thanks to Riyadul Karim and Dr Rageshri Dhairyawan for their review and thoughtful comments. South Asian Heritage Month was created in after Binita took part in the BBC1 documentary My Family, Partition and Me: India 1947 which features her father’s story.

- Diversity UK. Nurturing the Nation: the Asian contribution to the NHS

- South Asian Heath Foundation. Health inequalities: Full Stop